The Lost Child : David Ruben-Piqtoukun

Outside City Hall, Ottawa

The Lost Child by David Ruben-Piqtoukun, image courtesy City of Ottawa

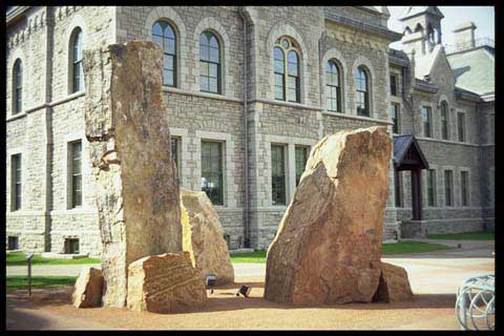

Jagged and roughly hewn, the six massive pieces of Kingston Hue sandstone cut a wild skyline at strange angles, seeming to grow from a square strewn with dull ruddy gravel. Hulking over the others in the middle of a vague half-circle and at a height of at least 20 feet, the tallest is flanked by a rugged duo of smaller stones. Approximately 12 feet high, another stands off to its side, flanked by a 3-foot high stone. Finally to the right of the central triad, an approximately 7-foot high stone completes the piece.

Dated 1989, it is the work of David Ruben-Piqtoukun. The plaque describes it as "the expression of the artist [from the North West Territories] as a young child visiting Edmonton with its overwhelming urban skyline". Certainly, it has that feel, especially given its surroundings. From one side, the Bell Park building on Elgin, with its beige stone and top to bottom stripes of beige concrete and glass and Barrister House in dark brown brick. It's placed directly in front of the newer Ottawa Carleton Center building, flanked by the fortress-like pale grey stone courthouse, and the 19th century grey-stone Heritage Building. Along with trees and picnic tables planted in perfect rows, bike racks have been placed haphazardly nearby.

Walking around it and in and out of it, I felt a certain awe. The stones reminded me of Stonehenge and, of course, the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. All speak to something eternal, something not quite known. Except unlike the former, The Lost Child is not set in some expansive English plain, and these stones, unlike the latter, hold their roughness dear.

But oddly the finished "pretty" look of their surroundings, their ordered clutter, and the architectural jumble, form a stark contrast to the blunt simplicity and durability of these stone giants. I felt as if the stones were in the wrong environment. Perhaps they need more room and less surrounding jumble to be fully appreciated, and yet it was this sense of displacement that led to other associations.

Bleached, encrusted, and worn by the elements and time, the stones enwrap themselves in rough surfaces. Mostly a dull orangey tone, you can see the layers of sediment that led to the stone's formation. Some sections even bear pale circles echoing tree rings, lending to a sense of perseverance, something that will endure.

Several years ago, a friend of mine grappling with the legacy of child abuse went into art therapy. In her first session, she was asked to draw what came to mind first when thinking about her abuse. From edge to edge to edge to edge, the entire sheet of paper was covered with a brick wall.

In session two, the therapist suggested she speak to the wall, befriend it, and slowly begin to ask it if, piece by piece, she could take it down....

On a plaque in front of his sculpture, artist Ruben-Piqtoukun is quoted as saying, "We have all been lost at some point in our lives."

Published in The Ottawa Citizen

Dated 1989, it is the work of David Ruben-Piqtoukun. The plaque describes it as "the expression of the artist [from the North West Territories] as a young child visiting Edmonton with its overwhelming urban skyline". Certainly, it has that feel, especially given its surroundings. From one side, the Bell Park building on Elgin, with its beige stone and top to bottom stripes of beige concrete and glass and Barrister House in dark brown brick. It's placed directly in front of the newer Ottawa Carleton Center building, flanked by the fortress-like pale grey stone courthouse, and the 19th century grey-stone Heritage Building. Along with trees and picnic tables planted in perfect rows, bike racks have been placed haphazardly nearby.

Walking around it and in and out of it, I felt a certain awe. The stones reminded me of Stonehenge and, of course, the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. All speak to something eternal, something not quite known. Except unlike the former, The Lost Child is not set in some expansive English plain, and these stones, unlike the latter, hold their roughness dear.

But oddly the finished "pretty" look of their surroundings, their ordered clutter, and the architectural jumble, form a stark contrast to the blunt simplicity and durability of these stone giants. I felt as if the stones were in the wrong environment. Perhaps they need more room and less surrounding jumble to be fully appreciated, and yet it was this sense of displacement that led to other associations.

Bleached, encrusted, and worn by the elements and time, the stones enwrap themselves in rough surfaces. Mostly a dull orangey tone, you can see the layers of sediment that led to the stone's formation. Some sections even bear pale circles echoing tree rings, lending to a sense of perseverance, something that will endure.

Several years ago, a friend of mine grappling with the legacy of child abuse went into art therapy. In her first session, she was asked to draw what came to mind first when thinking about her abuse. From edge to edge to edge to edge, the entire sheet of paper was covered with a brick wall.

In session two, the therapist suggested she speak to the wall, befriend it, and slowly begin to ask it if, piece by piece, she could take it down....

On a plaque in front of his sculpture, artist Ruben-Piqtoukun is quoted as saying, "We have all been lost at some point in our lives."

Published in The Ottawa Citizen