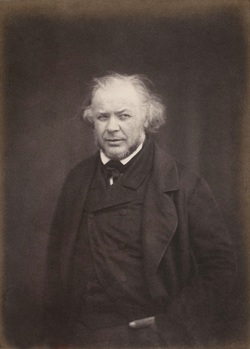

Honoré Daumier

National Gallery of Canada

By Victor Laisné or Lainé (1830-1911)

In the winter of 1878, it was possible to go to the Galeries Durand-Ruel in Paris and, for a franc, see the first retrospective of Honoré Daumier's work. For the first time the significance of his painting was acknowledged, and it was seen together with his drawings, watercolours, sculptures and satirical lithographs. Organized by his great artistic and literary friends, Daumier (1808-1879) was perhaps led through the show by his wife, for by then, he had almost lost his eyesight entirely.

Since then "Daumier has been split into little bits," explains Michael Pantazzi, co-curator of the National Gallery exhibit, describing the piecemeal exhibitions of Daumier's work by media. "We're trying for once, to put him back together again just as he was. He was not a schizophrenic!" he adds laughing, in typical Pantazzi style.

At the end of the Degas show in 1988, Pantazzi discussed the idea with his friend and colleague, Henri Loyrette, then a curator at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. Each had noted that Degas was yet another artist heavily influenced by Daumier.

A co-production of the National Gallery, the Musée d'Orsay and The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., Pantazzi and Loyrette ended up co-curating the show, but the National Gallery, under Pantazzi's direction, took care of its entire administration and the hanging of the work.

Pantazzi coughs occasionally. He's suffering from bronchitis. His fridge is empty. He's struggled to work because lying in bed is sheer misery, but he's absolutely determined that this interview will happen.

"The administration"—well. That's a poor description of a gargantuan task involving everyone from exhibition managers, senior administrators, designers, and technical staff, something that must've turned a few hairs grey. Laughing uproariously, Pantazzi says, "I have only a few hairs left! And they're all grey!"

Refreshingly self-effacing and grounded, Pantazzi humbly lays the entire credit for the success of the show where it should be—at Daumier's feet.

Regardless, perhaps more so than in Daumier's time, putting together this exhibition required more than this from the resourceful Associate Curator of European Art.

One hundred and two institutions and private collectors scattered throughout the world lent work to the show. For Pantazzi, this meant some eight years ago, he traveled the world, with suitcase and passport in hand and a precise vision worked out with Loyrette of what the exhibit could be, meeting with every single potential lender. The vision was of paramount importance since Daumier's prolific output gave no shortage of choices—4,000 lithographs, over 250 paintings, more than 800 drawings and about 1,000 woodcuts—covering subjects as diverse as human existence can be.

Convincing lenders to part for some 18 months with a treasured piece of a personal collection or in the case of institutions, perhaps part of their permanent collection on display, required astute diplomacy. This was particularly so since the concentrations of Daumier in some collections meant requesting more than the usual number of works. "If you explain very clearly what you are doing," says Pantazzi, "exactly why you need this particular work…people take your request much more seriously."

While no money changes hands for the loans, owners, especially those who have never lent to the Gallery before, were understandably nervous. The latter, in particular, Pantazzi admits, made him sweat. The bid to woo them included the shipping of a 240-page document Pantazzi prepared detailing every possible concern or possible emergency. It included information like: the temperature and humidity fluctuations every day in the galleries for the past year; the number of security guards per square foot; whether the fire extinguishers use water or halon, and the plans for Y2K (even though the exhibit will not be here then).

All this was done before a loan was even agreed to.

Five years ago letters were written advising potential lenders the Gallery would be mounting this show in 1999, tipping them off not to loan the work to anyone else. Depending on the medium and the work's condition, the time it can be displayed for is limited. Since the show will be going to Paris and Washington, arrangements for replacements had to be made, multiplying by three the amount of work required.

After insurance, conservation shipping and cost-sharing agreements were worked out on a per painting/sculpture/print basis, the agreements could run anywhere from 50-100 pages.

"The boredom, the tediousness of having to negotiate all these papers," groans Pantazzi, "I cannot tell you! But it's a small price to pay, if in some way he becomes part of public consciousness like Dickens is or was, or like Virginia Woolf ten years ago".

And yet, for more than 100 years, no one has taken the trouble to do all this. "I chose to do it because I liked him! I chose to do it because I thought somebody had to do it!" Pantazzi insists, adding, that since the Gallery (i.e. Canadians) own, for instance, The Third Class Carriage, one of Daumier's "most famous and beautiful pictures in some way, there was a responsibility."

While agreements were worked out, Pantazzi planned where each of the more than 300 pieces would be hung. Decisions were made about grouping the work, the placement of walls, their colour - each one, however small, had a cumulative impact that would be revealed only after the show was completely hung, a process that took about a week.

Given that insurance budgets increase the longer the work is under the Gallery's roof, the work is received as near to the opening as possible. Depending on the loan agreement, the courier's presence, a conservator, a "doctor of painting" as Pantazzi describes it, is required when the case is opened. On opening, the courier makes an examination including every detail of its condition, comparing it to the one made before shipping, and the new report is signed. In some cases, the doctor of painting has to be present while the work is hung. Subsequently, the work cannot be moved until the show is taken down. (This procedure is repeated when the show is dismantled.) Pantazzi's self-acknowledged skill in visualizing the exhibition before it even went up came into its own here.

Even so, he admits, "there are a few moments when your heart leaps." Will the wall's colours "be friendly to the work? As it comes out of the crate, you sort of tell yourself, alright, I decided this will be in the blue room, but it's a blue background…will the blue kill it? You trepidate for a few moments," he adds.

Two nights before the opening Loyrette arrived from Paris. As Pantazzi had foreseen, Loyrette rang him up from his hotel. He had also waited years to see it and could not wait until tomorrow - even if it meant going through the back door. "I don't want to see how it ends, I want to see it from the beginning!" Loyrette implored Pantazzi to lead him, while he covered his eyes with his hands. "When we got to about three galleries before the beginning," recalls Pantazzi, "I could see through the corner of my eye, that he had parted his fingers, and he was peeping!" Pantazzi laughs. Finally Loyrette let his hands fall, standing still, "absolutely thunderstruck, saying 'I never thought it would be so beautiful! It's beautiful!!' I thought well, baby, it took a long time, but there you are."

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 1999

Since then "Daumier has been split into little bits," explains Michael Pantazzi, co-curator of the National Gallery exhibit, describing the piecemeal exhibitions of Daumier's work by media. "We're trying for once, to put him back together again just as he was. He was not a schizophrenic!" he adds laughing, in typical Pantazzi style.

At the end of the Degas show in 1988, Pantazzi discussed the idea with his friend and colleague, Henri Loyrette, then a curator at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. Each had noted that Degas was yet another artist heavily influenced by Daumier.

A co-production of the National Gallery, the Musée d'Orsay and The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., Pantazzi and Loyrette ended up co-curating the show, but the National Gallery, under Pantazzi's direction, took care of its entire administration and the hanging of the work.

Pantazzi coughs occasionally. He's suffering from bronchitis. His fridge is empty. He's struggled to work because lying in bed is sheer misery, but he's absolutely determined that this interview will happen.

"The administration"—well. That's a poor description of a gargantuan task involving everyone from exhibition managers, senior administrators, designers, and technical staff, something that must've turned a few hairs grey. Laughing uproariously, Pantazzi says, "I have only a few hairs left! And they're all grey!"

Refreshingly self-effacing and grounded, Pantazzi humbly lays the entire credit for the success of the show where it should be—at Daumier's feet.

Regardless, perhaps more so than in Daumier's time, putting together this exhibition required more than this from the resourceful Associate Curator of European Art.

One hundred and two institutions and private collectors scattered throughout the world lent work to the show. For Pantazzi, this meant some eight years ago, he traveled the world, with suitcase and passport in hand and a precise vision worked out with Loyrette of what the exhibit could be, meeting with every single potential lender. The vision was of paramount importance since Daumier's prolific output gave no shortage of choices—4,000 lithographs, over 250 paintings, more than 800 drawings and about 1,000 woodcuts—covering subjects as diverse as human existence can be.

Convincing lenders to part for some 18 months with a treasured piece of a personal collection or in the case of institutions, perhaps part of their permanent collection on display, required astute diplomacy. This was particularly so since the concentrations of Daumier in some collections meant requesting more than the usual number of works. "If you explain very clearly what you are doing," says Pantazzi, "exactly why you need this particular work…people take your request much more seriously."

While no money changes hands for the loans, owners, especially those who have never lent to the Gallery before, were understandably nervous. The latter, in particular, Pantazzi admits, made him sweat. The bid to woo them included the shipping of a 240-page document Pantazzi prepared detailing every possible concern or possible emergency. It included information like: the temperature and humidity fluctuations every day in the galleries for the past year; the number of security guards per square foot; whether the fire extinguishers use water or halon, and the plans for Y2K (even though the exhibit will not be here then).

All this was done before a loan was even agreed to.

Five years ago letters were written advising potential lenders the Gallery would be mounting this show in 1999, tipping them off not to loan the work to anyone else. Depending on the medium and the work's condition, the time it can be displayed for is limited. Since the show will be going to Paris and Washington, arrangements for replacements had to be made, multiplying by three the amount of work required.

After insurance, conservation shipping and cost-sharing agreements were worked out on a per painting/sculpture/print basis, the agreements could run anywhere from 50-100 pages.

"The boredom, the tediousness of having to negotiate all these papers," groans Pantazzi, "I cannot tell you! But it's a small price to pay, if in some way he becomes part of public consciousness like Dickens is or was, or like Virginia Woolf ten years ago".

And yet, for more than 100 years, no one has taken the trouble to do all this. "I chose to do it because I liked him! I chose to do it because I thought somebody had to do it!" Pantazzi insists, adding, that since the Gallery (i.e. Canadians) own, for instance, The Third Class Carriage, one of Daumier's "most famous and beautiful pictures in some way, there was a responsibility."

While agreements were worked out, Pantazzi planned where each of the more than 300 pieces would be hung. Decisions were made about grouping the work, the placement of walls, their colour - each one, however small, had a cumulative impact that would be revealed only after the show was completely hung, a process that took about a week.

Given that insurance budgets increase the longer the work is under the Gallery's roof, the work is received as near to the opening as possible. Depending on the loan agreement, the courier's presence, a conservator, a "doctor of painting" as Pantazzi describes it, is required when the case is opened. On opening, the courier makes an examination including every detail of its condition, comparing it to the one made before shipping, and the new report is signed. In some cases, the doctor of painting has to be present while the work is hung. Subsequently, the work cannot be moved until the show is taken down. (This procedure is repeated when the show is dismantled.) Pantazzi's self-acknowledged skill in visualizing the exhibition before it even went up came into its own here.

Even so, he admits, "there are a few moments when your heart leaps." Will the wall's colours "be friendly to the work? As it comes out of the crate, you sort of tell yourself, alright, I decided this will be in the blue room, but it's a blue background…will the blue kill it? You trepidate for a few moments," he adds.

Two nights before the opening Loyrette arrived from Paris. As Pantazzi had foreseen, Loyrette rang him up from his hotel. He had also waited years to see it and could not wait until tomorrow - even if it meant going through the back door. "I don't want to see how it ends, I want to see it from the beginning!" Loyrette implored Pantazzi to lead him, while he covered his eyes with his hands. "When we got to about three galleries before the beginning," recalls Pantazzi, "I could see through the corner of my eye, that he had parted his fingers, and he was peeping!" Pantazzi laughs. Finally Loyrette let his hands fall, standing still, "absolutely thunderstruck, saying 'I never thought it would be so beautiful! It's beautiful!!' I thought well, baby, it took a long time, but there you are."

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 1999