Researcher's Notes

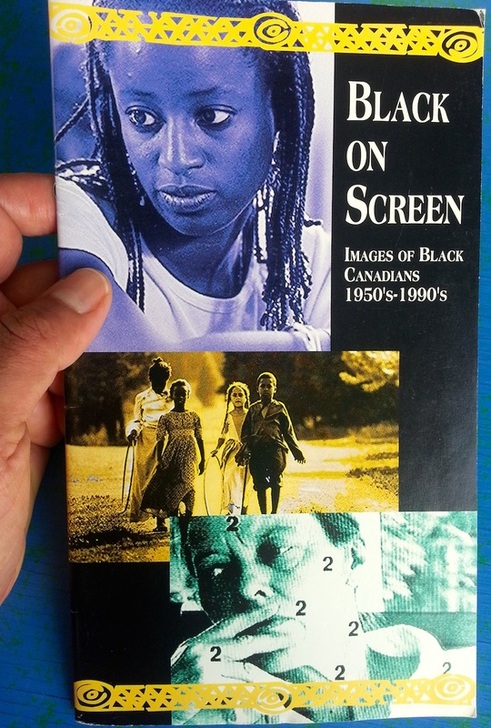

Black on Screen: 1950s to 1990s, Images of Black Canadians

A film and video catalogue

Published by the National Film Board of Canada, 1992

Photograph of Black on Screen, Molly Amoli K. Shinhat

While working on this project, I have become an aunt for the first time. For Kiran, my niece, both my sister and I have been looking for toys and children's literature that includes or focuses on the lives of people of colour. Needless to say, it has been an arduous task. In my niece's lifetime, the hegemony of technology, surveillance, and information control, may force us to monitor and analyze ever more closely what kinds of information and cultural products we are denied will grow. It was imagining this possible future, which bore more than a passing resemblance to my own present and past, that informed my approach to this project. Many times I have wondered what mirrors, constructed and held up by whom, will be thrust before my niece as she begins her own journey of self-discovery. Will she, like so many before her, have to go through the same devastations, emerging healed but bearing scars of the voyage?

In its first incarnation as a pamphlet accompanying the release of the Studio D film Sisters in the Struggle, the aim was to find the broadest collection possible of work about themes addressed in that film. To that end some NFB and non-NFB catalogues were consulted, and a FORMAT search was conducted under general categories like history, women, work and labor relations, settlements, culture, multiculturalism, immigration, and racism, discrimination, arts, employment, and so on.

Subsequently a Canada-wide call was made to independent film and video distributors (herein referred to as "distributors") and filmmakers. The initial response included comments from some distributors asking why the Studio did not reference Black British or Black American work, followed by statements that there was not much work available that was made by Black Canadians. Even though there was indeed work available (in formal distribution structures) by Black Canadian film- and video-makers, and plenty of archival and contemporary work made by people outside the Black communities, no single distributor contqcted by Studio D at that time had a package, catalogue, or suggested formal program specifically about Black Canadian experiences. The only exceptions were the smaller local programs and the requisite "Black History Month Bonanzas."

Three main FORMAT searches were initiated. On the basis of the first and a list of major distributors, a form letter describing the project and information being sought was sent to approximately thirty distributors, directors and production houses (where appropriate) in February 1992. The catalogue grew through responses to that initial mail-out which included numerous catalogues, phone conversations, leads from a range of people of various backgrounds—all of which led to additional requests for information.

In its entirety the research took about one year. The mainstay of the process was FORMAT, the Canadian Audiovisual Database, available at the National Film Board. This database covers all NFB-produced work since 1939 and non-NFB work since 1980, the year the National Library and National Archives began to fund the non-NFB portion of the database.

The job was sometimes the work of a detective—to find work that had seemingly been hidden or forgotten or that relatively few people knew about or that previous researches had been unable to get to for any number of reasons—especially, for example, in cases where the practitioner had no formals distribution process in place. In part the difficulty in finding work can also definitely be attributed to the harsh funding realities faced by Black Canadian film- and video-makers. Small production budgets may translate into small or non-existent budgets for distribution. This collection therefore is not definitive. Some films and videos could not be traced; others are still in production.

Additional FORMAT searches were initiated because several seemingly appropriate NFB and non-NFB titles did not appear on the initial list. New titles came up on subsequent searches even though they were not recent productions.

In the FORMAT database, subject headings are allocated based on the production's description as given to FORMAT by the producer and/or distributor. Usually the distributor does not submit a copy of the work to screen for indexing purposes. As often as posibble FORMAT staff still try to screen before indexing. However this is more likely for NFB-produced rather than non-NFB produced work because of the sheer logistics and cost of obtaining screening copies of all Canadian productions per year (on average approximately 2,000).

This indexing procedure has had obvious implications for the research. The lack of attention given to this aspect of distribution by the producers and/or directors and/or distributors can mean there may be hundreds of productions that we may never know of.

The distributors' indexing systems are on the whole unique to each organization. After going through catalogues and asking distribution personnel for any additional titles, still there were occasions where I found work that had not been mentioned. This happened despite the fact that many distribution personnel knew the organization's collection. In some cases, one individual both structures and places work in the system. Who determines which individual or group of people structures the indexing system and places work in it? If it is an individual, what happens when that person leaves? I am unsure if a standardized national indexing system for all distributors would be an answer. It raises all too many questions, perhaps the most important being: who would devise such a system?

The headings themselves presented another dilemma. Culture and racial-ethnic identities in their relationship to subjects who are also "Canadian"—even in the legal sense of the latter—rarely came together in subject headings. Several titles about the experiences of Black Canadians were found under that all-embraciing heading, "immigration." Thematically these films were not about migration or immigration. Apparently the people responsible for indexing through it appropriate since they perceived the Black Canadian communities as "immigrants". "Multiculturalism" was the other problematic category, under which any production content that was non-Euyropean in origin was listed. What does "multiculturalism" mean in this context? That European subject matter is by definition "uni-cultural" since it is "The (Dominant) Culture"? That our cultures, the cultures of people of colour, are deemed so fragmented that films or videos about our experiences could not be indexed under "Culture"?

This issue of race in its relationship to nationality—even in the strictest legal sense of the latter—became even more problematic. Oliver Jones in Africa and Unnatural Causes did not appear in any FORMAT search. A FORMAT printout was requested however to get full technical information on each film. Oliver Jones in Africa was listed under the following précis subject index, "Africa, musicians, visits by Canadian jazz pianist, Jones, Oliver" and Unnatural Causes under "Canadian poetry in English, Allen, Lillian, special themes; Canada, social problems—film adaptations." "Africa" and "Canadian" do not appear connected in any way, nor is there any appropriate variation like, for example, "Canadians of African-descent" of "Black Canadians" or Black Canadian cultures(s)". Unless one knew otherwise, one would not know that the featured work was that of or about a Black Canadian. It is almost as if the two words together are an oxymoron within the FORMAT (and other) index systems. In FORMAT I am told that unless a racial aspect to the subject is clearly stated in the production's description and/or subject indexes are suggested, the film will not filed under any index whereby it could be traced in terms of its racial or cultural content or context.

The placement of material under racial-ethnic categories in terms of its subject and/or director cannot possibly be seen as "The Solution". To do so many create a reason for some to ignore the material entirely. Besides listing all work by directors of colour under one heading, "Race" for example, a procedure being used at some distributors, there has to be another way to increase the accessibility to this work.

Both Canada's major television networks have produced numerous programs ranging from portraits of Black Canadian artists to two-minute news items and discussions focusing on the latest "hot spot" in the Black Canadian communities. Because of a variety of factors, it was often not possible to list the programs in the catalogue. Both networks understood "distributors" in its formal sense, and so unless a structure was already in place for a production, it could not be listed in this catalogue. CTV, for example, produced and is listed as distributor (in FORMAT) for Policing the Cops, a program that looks at what happened after the fatal shooting of Anthony Griffin, a young Black man, by a Montreal Urban Community policeman in November 1987. Due to various rights problems with material in the production, CTV did not give permission to include it in the catalogue because it has never been cleared for (auxiliary) external non-broadcast use. Lincoln Alexander was suggested for the catalogue instead.

As with CTV, CBC could not give permission to list certain materials. In the case of Jodie Drake: Blues in my Bread (dir. Christene Browne, 1992), the producer said that since CBC does not own the rights to all of the music featured in the production, it cannot be listed as "distributor." The formalization of "distributor" led to problems with the other institutions through which CBC or CTV-produced work is available. For example, Mom Suze in twenty-seven minutes profiles a 103 year-old Black woman, born and raised in Preston, Nova Scotia. Produced by CBC Halifax, the tape is available, with certain restrictions, through Nova Scotia Education media Services (NSEMS). NSEMS however did not give permission to include it because it does not have a formal distribution agreement with the CBC. (At CBC it is possible to informally screen material at most stations. CTV does not offer this service and usually does not sell copies of material it distributes to individuals. Both organizations have catalogues of work they do distribute. For more information, contact the networks of the addresses listed at the back of this catalogue.)

I only hope that this catalogue provides one person with stories or images or affirmations or knowledge or material for analysis hitherto denied or inaccessible. Reward greater than that would only be to live to see the necessity for this kind of catalogue become obsolete.

I would like to thank all the individuals who took time to answer my many questions. For their various kind s of contributions to this project, I would especially like to thank: Charmaine Dayle, Jane Devine, Anne Golden, Barbara Goslawski, Sylvia Hamilton, Betty Julian, Colette Lebeuf, Stephen Park, and Wanda Vanderstoop. I gratefully acknowledge the love, support and patience of my friends and family, particularly Surjit Kaur and Harchand Singh, my parents and my sister Dolly, all of whose perspectives were invaluable. I express my deepest gratitude to Kiran Eleanor Simran Ross, my six-month old niece, and to my new friend, Bhima.

Published in Black on Screen, 1992

In its first incarnation as a pamphlet accompanying the release of the Studio D film Sisters in the Struggle, the aim was to find the broadest collection possible of work about themes addressed in that film. To that end some NFB and non-NFB catalogues were consulted, and a FORMAT search was conducted under general categories like history, women, work and labor relations, settlements, culture, multiculturalism, immigration, and racism, discrimination, arts, employment, and so on.

Subsequently a Canada-wide call was made to independent film and video distributors (herein referred to as "distributors") and filmmakers. The initial response included comments from some distributors asking why the Studio did not reference Black British or Black American work, followed by statements that there was not much work available that was made by Black Canadians. Even though there was indeed work available (in formal distribution structures) by Black Canadian film- and video-makers, and plenty of archival and contemporary work made by people outside the Black communities, no single distributor contqcted by Studio D at that time had a package, catalogue, or suggested formal program specifically about Black Canadian experiences. The only exceptions were the smaller local programs and the requisite "Black History Month Bonanzas."

Three main FORMAT searches were initiated. On the basis of the first and a list of major distributors, a form letter describing the project and information being sought was sent to approximately thirty distributors, directors and production houses (where appropriate) in February 1992. The catalogue grew through responses to that initial mail-out which included numerous catalogues, phone conversations, leads from a range of people of various backgrounds—all of which led to additional requests for information.

In its entirety the research took about one year. The mainstay of the process was FORMAT, the Canadian Audiovisual Database, available at the National Film Board. This database covers all NFB-produced work since 1939 and non-NFB work since 1980, the year the National Library and National Archives began to fund the non-NFB portion of the database.

The job was sometimes the work of a detective—to find work that had seemingly been hidden or forgotten or that relatively few people knew about or that previous researches had been unable to get to for any number of reasons—especially, for example, in cases where the practitioner had no formals distribution process in place. In part the difficulty in finding work can also definitely be attributed to the harsh funding realities faced by Black Canadian film- and video-makers. Small production budgets may translate into small or non-existent budgets for distribution. This collection therefore is not definitive. Some films and videos could not be traced; others are still in production.

Additional FORMAT searches were initiated because several seemingly appropriate NFB and non-NFB titles did not appear on the initial list. New titles came up on subsequent searches even though they were not recent productions.

In the FORMAT database, subject headings are allocated based on the production's description as given to FORMAT by the producer and/or distributor. Usually the distributor does not submit a copy of the work to screen for indexing purposes. As often as posibble FORMAT staff still try to screen before indexing. However this is more likely for NFB-produced rather than non-NFB produced work because of the sheer logistics and cost of obtaining screening copies of all Canadian productions per year (on average approximately 2,000).

This indexing procedure has had obvious implications for the research. The lack of attention given to this aspect of distribution by the producers and/or directors and/or distributors can mean there may be hundreds of productions that we may never know of.

The distributors' indexing systems are on the whole unique to each organization. After going through catalogues and asking distribution personnel for any additional titles, still there were occasions where I found work that had not been mentioned. This happened despite the fact that many distribution personnel knew the organization's collection. In some cases, one individual both structures and places work in the system. Who determines which individual or group of people structures the indexing system and places work in it? If it is an individual, what happens when that person leaves? I am unsure if a standardized national indexing system for all distributors would be an answer. It raises all too many questions, perhaps the most important being: who would devise such a system?

The headings themselves presented another dilemma. Culture and racial-ethnic identities in their relationship to subjects who are also "Canadian"—even in the legal sense of the latter—rarely came together in subject headings. Several titles about the experiences of Black Canadians were found under that all-embraciing heading, "immigration." Thematically these films were not about migration or immigration. Apparently the people responsible for indexing through it appropriate since they perceived the Black Canadian communities as "immigrants". "Multiculturalism" was the other problematic category, under which any production content that was non-Euyropean in origin was listed. What does "multiculturalism" mean in this context? That European subject matter is by definition "uni-cultural" since it is "The (Dominant) Culture"? That our cultures, the cultures of people of colour, are deemed so fragmented that films or videos about our experiences could not be indexed under "Culture"?

This issue of race in its relationship to nationality—even in the strictest legal sense of the latter—became even more problematic. Oliver Jones in Africa and Unnatural Causes did not appear in any FORMAT search. A FORMAT printout was requested however to get full technical information on each film. Oliver Jones in Africa was listed under the following précis subject index, "Africa, musicians, visits by Canadian jazz pianist, Jones, Oliver" and Unnatural Causes under "Canadian poetry in English, Allen, Lillian, special themes; Canada, social problems—film adaptations." "Africa" and "Canadian" do not appear connected in any way, nor is there any appropriate variation like, for example, "Canadians of African-descent" of "Black Canadians" or Black Canadian cultures(s)". Unless one knew otherwise, one would not know that the featured work was that of or about a Black Canadian. It is almost as if the two words together are an oxymoron within the FORMAT (and other) index systems. In FORMAT I am told that unless a racial aspect to the subject is clearly stated in the production's description and/or subject indexes are suggested, the film will not filed under any index whereby it could be traced in terms of its racial or cultural content or context.

The placement of material under racial-ethnic categories in terms of its subject and/or director cannot possibly be seen as "The Solution". To do so many create a reason for some to ignore the material entirely. Besides listing all work by directors of colour under one heading, "Race" for example, a procedure being used at some distributors, there has to be another way to increase the accessibility to this work.

Both Canada's major television networks have produced numerous programs ranging from portraits of Black Canadian artists to two-minute news items and discussions focusing on the latest "hot spot" in the Black Canadian communities. Because of a variety of factors, it was often not possible to list the programs in the catalogue. Both networks understood "distributors" in its formal sense, and so unless a structure was already in place for a production, it could not be listed in this catalogue. CTV, for example, produced and is listed as distributor (in FORMAT) for Policing the Cops, a program that looks at what happened after the fatal shooting of Anthony Griffin, a young Black man, by a Montreal Urban Community policeman in November 1987. Due to various rights problems with material in the production, CTV did not give permission to include it in the catalogue because it has never been cleared for (auxiliary) external non-broadcast use. Lincoln Alexander was suggested for the catalogue instead.

As with CTV, CBC could not give permission to list certain materials. In the case of Jodie Drake: Blues in my Bread (dir. Christene Browne, 1992), the producer said that since CBC does not own the rights to all of the music featured in the production, it cannot be listed as "distributor." The formalization of "distributor" led to problems with the other institutions through which CBC or CTV-produced work is available. For example, Mom Suze in twenty-seven minutes profiles a 103 year-old Black woman, born and raised in Preston, Nova Scotia. Produced by CBC Halifax, the tape is available, with certain restrictions, through Nova Scotia Education media Services (NSEMS). NSEMS however did not give permission to include it because it does not have a formal distribution agreement with the CBC. (At CBC it is possible to informally screen material at most stations. CTV does not offer this service and usually does not sell copies of material it distributes to individuals. Both organizations have catalogues of work they do distribute. For more information, contact the networks of the addresses listed at the back of this catalogue.)

I only hope that this catalogue provides one person with stories or images or affirmations or knowledge or material for analysis hitherto denied or inaccessible. Reward greater than that would only be to live to see the necessity for this kind of catalogue become obsolete.

I would like to thank all the individuals who took time to answer my many questions. For their various kind s of contributions to this project, I would especially like to thank: Charmaine Dayle, Jane Devine, Anne Golden, Barbara Goslawski, Sylvia Hamilton, Betty Julian, Colette Lebeuf, Stephen Park, and Wanda Vanderstoop. I gratefully acknowledge the love, support and patience of my friends and family, particularly Surjit Kaur and Harchand Singh, my parents and my sister Dolly, all of whose perspectives were invaluable. I express my deepest gratitude to Kiran Eleanor Simran Ross, my six-month old niece, and to my new friend, Bhima.

Published in Black on Screen, 1992