Ave Mater

José Mansilla-Miranda

Centre d'Exposition Art-Image

Maison de la culture de Gatineau

Image copyright Espace Virtuel

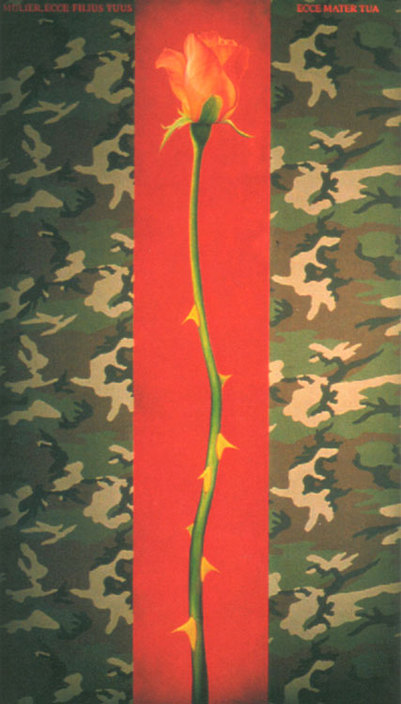

The three large panels along one side dominate the dimly lit gallery. Dividing each canvas into three vertical stripes, painter José Mansilla-Miranda uses camouflage to flank a central stripe featuring a rose. In the first, the rose's head droops downward. In the second, the rose, about to bloom, is revealed complete with thorns. The third painting features two roses growing from the same stem, one a closed bud, with leaves falling down, resonating with the camouflage.

Before each panel on the floor, lies a piece of white net, eerily shroud-like. A prayer stand, covered with another piece of white net and a priest's bands, faces the three paintings. Standing behind it, the view is modulated only by an intravenous drip from which a red liquid has collected in a chalice on the floor. A small mound of earth shaped like a piece of land lies spreads out from below the chalice.

Deceptively simple, it's an enigmatic installation that almost despite highly charged elements—very realistic looking blood for instance - gently draws the viewer in with its spare eloquent and carefully designed lighting along with calming vocal music.

"I started to create this idea of a chapel, just for myself, just to understand my own concept of praying," says Mansilla-Miranda. "As a visual artist I decided to contemplate my own background and my own ideas."

A former Catholic priest associated with the Theology of Liberation, Mansilla-Miranda escaped from Chile to Argentina after three brothers in his order were shot and killed.

Dedicating Ave Mater ("Hail Mother") to the mothers of the countless Disappeared of Latin America, the modulated scarlet-blood-red alongside camouflage backgrounds in the paintings coagulate with the intravenous-chalice creating a multi-layered bold statement.

"I tried to deconstruct my own mind...colonized by the catechism of the Catholic Church—that I'm not allowed to create my own spiritual place. I tied this idea with the motherhood of Mary. That mother also lost her child in a political struggle with the Romans."

Critiquing the institutionalization of motherhood, he references the commoditization of the uterus through reproductive technologies in his artist's statement and briefly describes women's organizing around the Disappeared and its role in raising their own "ideological awareness of political and gender issues."

"The courage and moral force of these women is source of inspiration to build the millennium," Mansilla-Miranda writes. "These mothers are the living Revolutionary Icons of our times, whose wombs (chalice) are symbols of reconciliation, peace, love and life."

On the surface, this appears less than "revolutionary". Mansilla-Miranda evidently ditches his reputation as the iconoclast of "Rebel Icons" exhibition of 1997 donning the mantle of traditional religious iconographer. In this view, women are ideologically glorified, ultimately, because of breasts, vaginas, vulvas and uteri, i.e. symbols of nature writ large. Culture becomes the sole domain of men. The penultimate feminine act is procreation, one pole of the whore-Madonna model, so central to both our culture and the Catholic Church's ideology.

But Mansilla-Miranda's interpretation of Church doctrines inverts that perception.

"The motherhood of women was appropriated by the Catholic Church," says Mansilla-Miranda. "Because the mother of Christ, doesn't have sex, she has no uterus. That is my problem of the construction - I want to portray that Mary is a woman, like every woman on the planet."

"The Catholic Church says, 'I am the holy mother of everybody', but the mother doesn't have a uterus. How can you have a conception of a child without a uterus?"

Initially it seemed Mansilla-Miranda used Catholic symbols because of the Church's support of the women he pays homage to.

"It's an enormous support and a burden also," says Mansilla-Miranda of the Church, noting that about 90% of Latin Americans are Catholics. "The Catholic Church always condemns the choice of women to give birth. The Holy Virgin without a vagina never experienced pleasure, never experienced sex. You have sex you are condemned. But who rules the church? The men."

In using water with wine in the intravenous drip and the chalice, Mansilla-Miranda appropriates perhaps the most powerful of all Catholic symbols.

"The water of life is the power of sex, the power of semen. Using water and wine, I am recreating the mystical symbolism of the blood of Christ," he says. "I am feeding you medically, clinically, because you are injured - so I have to reconcile you, to heal you."

Manipulating Catholic ritual and symbolism, Mansilla-Miranda poses questions and raises concerns about religious practices and life in Latin America.

"'There is some mould that is growing on the chalice from the wine,' she told me," he says, recalling a phone call from the gallery a few days ago. "I said, 'That's perfect!' With time the wine starts to decay and mould. The real ritual of nature is there because mould is a new life...."

Published by The Ottawa Xpress, 2002

Before each panel on the floor, lies a piece of white net, eerily shroud-like. A prayer stand, covered with another piece of white net and a priest's bands, faces the three paintings. Standing behind it, the view is modulated only by an intravenous drip from which a red liquid has collected in a chalice on the floor. A small mound of earth shaped like a piece of land lies spreads out from below the chalice.

Deceptively simple, it's an enigmatic installation that almost despite highly charged elements—very realistic looking blood for instance - gently draws the viewer in with its spare eloquent and carefully designed lighting along with calming vocal music.

"I started to create this idea of a chapel, just for myself, just to understand my own concept of praying," says Mansilla-Miranda. "As a visual artist I decided to contemplate my own background and my own ideas."

A former Catholic priest associated with the Theology of Liberation, Mansilla-Miranda escaped from Chile to Argentina after three brothers in his order were shot and killed.

Dedicating Ave Mater ("Hail Mother") to the mothers of the countless Disappeared of Latin America, the modulated scarlet-blood-red alongside camouflage backgrounds in the paintings coagulate with the intravenous-chalice creating a multi-layered bold statement.

"I tried to deconstruct my own mind...colonized by the catechism of the Catholic Church—that I'm not allowed to create my own spiritual place. I tied this idea with the motherhood of Mary. That mother also lost her child in a political struggle with the Romans."

Critiquing the institutionalization of motherhood, he references the commoditization of the uterus through reproductive technologies in his artist's statement and briefly describes women's organizing around the Disappeared and its role in raising their own "ideological awareness of political and gender issues."

"The courage and moral force of these women is source of inspiration to build the millennium," Mansilla-Miranda writes. "These mothers are the living Revolutionary Icons of our times, whose wombs (chalice) are symbols of reconciliation, peace, love and life."

On the surface, this appears less than "revolutionary". Mansilla-Miranda evidently ditches his reputation as the iconoclast of "Rebel Icons" exhibition of 1997 donning the mantle of traditional religious iconographer. In this view, women are ideologically glorified, ultimately, because of breasts, vaginas, vulvas and uteri, i.e. symbols of nature writ large. Culture becomes the sole domain of men. The penultimate feminine act is procreation, one pole of the whore-Madonna model, so central to both our culture and the Catholic Church's ideology.

But Mansilla-Miranda's interpretation of Church doctrines inverts that perception.

"The motherhood of women was appropriated by the Catholic Church," says Mansilla-Miranda. "Because the mother of Christ, doesn't have sex, she has no uterus. That is my problem of the construction - I want to portray that Mary is a woman, like every woman on the planet."

"The Catholic Church says, 'I am the holy mother of everybody', but the mother doesn't have a uterus. How can you have a conception of a child without a uterus?"

Initially it seemed Mansilla-Miranda used Catholic symbols because of the Church's support of the women he pays homage to.

"It's an enormous support and a burden also," says Mansilla-Miranda of the Church, noting that about 90% of Latin Americans are Catholics. "The Catholic Church always condemns the choice of women to give birth. The Holy Virgin without a vagina never experienced pleasure, never experienced sex. You have sex you are condemned. But who rules the church? The men."

In using water with wine in the intravenous drip and the chalice, Mansilla-Miranda appropriates perhaps the most powerful of all Catholic symbols.

"The water of life is the power of sex, the power of semen. Using water and wine, I am recreating the mystical symbolism of the blood of Christ," he says. "I am feeding you medically, clinically, because you are injured - so I have to reconcile you, to heal you."

Manipulating Catholic ritual and symbolism, Mansilla-Miranda poses questions and raises concerns about religious practices and life in Latin America.

"'There is some mould that is growing on the chalice from the wine,' she told me," he says, recalling a phone call from the gallery a few days ago. "I said, 'That's perfect!' With time the wine starts to decay and mould. The real ritual of nature is there because mould is a new life...."

Published by The Ottawa Xpress, 2002