A Dialogue with Stone

Ingo Hessel

L'Alliance Française d'Ottawa-Hull

It feels like something from another planet and feeds the gnawing consciousness that we literally are loosing touch with the natural world. For at the same time as these are clearly manipulated, cleaned up, changed - Ingo Hessel's stone sculptures unveil caverns running back to some primordial space and time.

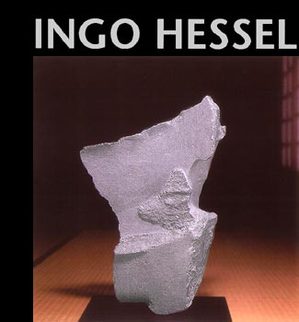

Fish/Mountain Transformation 2000, Virginia Soapstone. A singular piece of stone sits inside a shallow wooden box filled with light-coloured pebbles. Almost chameleon-like, the large dark-grey piece parades several textures, unlocking veins of dark orange where the stone has been worked. Scored on the top with a stippling-like texture along the side, some of the edges are polished smooth. While inherently organic, the shape bears evidence of intense trauma along its jagged edges. At about 36" long and 12" high, from the side, it does look like a fish. And yet, it really shows off its colours when you close your eyes and explore it with your hands (There are no signs on the walls forbidding the use of touch.).

A self-described "rock hound" in childhood, Ottawa-born Hessel forsook unearthing the secrets of stone as a scientist to develop a love of art and architecture. A Dialogue with Stone is the latest in what has for him become a lifelong relationship with bits of the earth's crust.

These twenty-six pieces feel like meditations extracted from sandstone, alabaster, granite and marble. Stone is transmutable in a way arguably unique to itself. Our lives are less than an eye-blink compared to the time required to form this material. The time taken to choose a piece of stone and make it into art is even less. Our interactions with stone can be as ephemeral as skimming a flat pebble across the surface of a lake or as irredeemable as boulders crashing down on people caught in an avalanche or mud slide.

Hessel's work drinks deeply from the rivers of our long and complex relationship with it. Why is it, for instance, that often people in crisis are drawn to structures built of stone, like temples, churches, or even cemeteries? Surely, part of the appeal, in the case of monumental stone architecture for instance, is the awareness that such structures endure and persevere. Perhaps it's also their eerie ability to reflect something of our own mystery and magnify it. After all the formidable structures were built by people, just like you and me.

One may be tempted to believe that stone sculptures, particularly of Hessel's type, would tend to miniaturize such themes. Strangely despite the obvious difference in scale, they do not. Hessel formerly worked at the Inuit Art Centre at the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs and is a consultant and well-known author on Inuit art. Its profound influence on him shows in the work.

With titles like Floating Island, Passages, Celestial Traveller, Voyager and Poseidon's Gift, Hessel appears to encourage both a compression and expansion of the sense of time ebbing out of his work. Many of the raw shapes he uses, while referencing the natural world—the marine world especially—lend themselves to a transposition on the future. Heavily manipulated textures along side smoothly polished surfaces envelop a shape that could as easily be a Devil Fish as some asteroid from another galaxy.

Unfortunately thought or perhaps resources were lacking in the works' presentation. Pushed right up against the walls, most pieces sit on pale unfinished wooden tables, and a few are well below eye level. These tables frequently detract visually and run ongoing interference with attempts to view the work. Other seemingly arbitrary presentation methods combined with the cream shade of the gallery walls only add to the visual white noise. The biggest lemon however, definitely goes to the fairly flat standard track lighting, used to little if no effect. If anything, it merely reduces the volume of the many voices and languages of these eloquent stone speakers.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000

Fish/Mountain Transformation 2000, Virginia Soapstone. A singular piece of stone sits inside a shallow wooden box filled with light-coloured pebbles. Almost chameleon-like, the large dark-grey piece parades several textures, unlocking veins of dark orange where the stone has been worked. Scored on the top with a stippling-like texture along the side, some of the edges are polished smooth. While inherently organic, the shape bears evidence of intense trauma along its jagged edges. At about 36" long and 12" high, from the side, it does look like a fish. And yet, it really shows off its colours when you close your eyes and explore it with your hands (There are no signs on the walls forbidding the use of touch.).

A self-described "rock hound" in childhood, Ottawa-born Hessel forsook unearthing the secrets of stone as a scientist to develop a love of art and architecture. A Dialogue with Stone is the latest in what has for him become a lifelong relationship with bits of the earth's crust.

These twenty-six pieces feel like meditations extracted from sandstone, alabaster, granite and marble. Stone is transmutable in a way arguably unique to itself. Our lives are less than an eye-blink compared to the time required to form this material. The time taken to choose a piece of stone and make it into art is even less. Our interactions with stone can be as ephemeral as skimming a flat pebble across the surface of a lake or as irredeemable as boulders crashing down on people caught in an avalanche or mud slide.

Hessel's work drinks deeply from the rivers of our long and complex relationship with it. Why is it, for instance, that often people in crisis are drawn to structures built of stone, like temples, churches, or even cemeteries? Surely, part of the appeal, in the case of monumental stone architecture for instance, is the awareness that such structures endure and persevere. Perhaps it's also their eerie ability to reflect something of our own mystery and magnify it. After all the formidable structures were built by people, just like you and me.

One may be tempted to believe that stone sculptures, particularly of Hessel's type, would tend to miniaturize such themes. Strangely despite the obvious difference in scale, they do not. Hessel formerly worked at the Inuit Art Centre at the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs and is a consultant and well-known author on Inuit art. Its profound influence on him shows in the work.

With titles like Floating Island, Passages, Celestial Traveller, Voyager and Poseidon's Gift, Hessel appears to encourage both a compression and expansion of the sense of time ebbing out of his work. Many of the raw shapes he uses, while referencing the natural world—the marine world especially—lend themselves to a transposition on the future. Heavily manipulated textures along side smoothly polished surfaces envelop a shape that could as easily be a Devil Fish as some asteroid from another galaxy.

Unfortunately thought or perhaps resources were lacking in the works' presentation. Pushed right up against the walls, most pieces sit on pale unfinished wooden tables, and a few are well below eye level. These tables frequently detract visually and run ongoing interference with attempts to view the work. Other seemingly arbitrary presentation methods combined with the cream shade of the gallery walls only add to the visual white noise. The biggest lemon however, definitely goes to the fairly flat standard track lighting, used to little if no effect. If anything, it merely reduces the volume of the many voices and languages of these eloquent stone speakers.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000