Tang Ren Jie

A Living Archive

This year's Festival of Chinese Film in Montreal included an accompanying photo exhibition,

Tang Ren Jie, which documented over 100 years of the Chinese community in Montreal

Three years ago in Montreal Tammy Cheung borrowed 14 Chinese films and presented a mini film festival. At the time she was a foreign student from Hong Kong studying cinema in Montreal and working as a community worker for the Chinese Neighbourhood Society of Montreal. Part of that included organizing a "variety show" to celebrate the Chinese New Year. From that first year the variety show-cum-festival eventually grew to become the Festival International du Cinéma Chinois de Montréal (FICCM), Cheung co-directing with Lori McLean and Heidi Miller.

The annual festival continues to be the main activity of InterCineArt, a group dedicated to promoting cross-cultural understanding. Teh festival's scope expands each year in terms of its programming. This year's edition featured over 80 films and videos from Hong Kong, Chinda, Taiwan, Canada, U.S., England and Japan.

The eclectic selection, which included documentaries, full-length features, commercial films and TV items from current affairs programs, was further augmented by a group of films made in the 1930s, '40s and '50s in mainland China, providing audiences with a rare chance to see some early masterpieces of Chinese cinema such as Yuan Muzhi's Street Angel (1937), Zheng Junli's Crows and Sparrows (1949) and Fate of a Graduate by Ying Yunei (1934).

The events of June 4, 1989 in Tianamen Square had a definite impact on this year's programming. Michael Gilson, who programmed with Cheung, says it was difficult not knowing what would be available. An attempt to get Black Snow by Xie Fei (1990), one fo the few films known to be made after June 4, failed. Samsara (dir. Huang Ianxin, 1989), screened this year to packed houses, has been banned by the Chinese government although it had received praise from the public. The film focuses on the disillusionment and later demise of Shi Ba, the son of a high-ranking official. The exact number of prints in circulation of Samsara is not known, but it is thought that the festival's copy is one of two or three presently not in China.

This year for the first time, part of the festival moved on to another city—six films were screened at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, Quebec. While the Secretary of State has encouraged the festival to expand, organizers say that expansion cannot proceed without increased funding.

During the year there are two grant-subsidized positions. These positions expanded to five during the festival. This year's festival would not have been possible without the volunteer labour of some 25 Montrealers of various backgrounds.

In a recent interview, Cheung voice some of her outstanding concerns, most of which centre on community involvement. Unlike many other film festivals, the FICCM has not experienced any major difficulties in attracting Chinese viewers and security in the on-going support and interest of Montreal's Asian communities. This year they averaged about 60 per cent of the audiences. Cheung would like to see greater involvement, however, at the organizational level and moves are being made in this regard. Closer bonds between FICCM and grassroots communities are becoming evident. As usual, the festival's schedule was published in full in The Chinese Press (the highest circulation Chinese language newspaper in Quebec). Posters and schedules were also distributed by hand in Chinatown.

This year's accompanying photo exhibition, Tang Ren Jie, looked at the history of Chinese presence in Montreal. Produced by InterCineArt, it was displayed outdoors in Chinatown for three days in Sun Yat-Sen Park and later moved indoors to Complexe Guy Favreau for 12 more days. All told, an estimated 8,000 people saw the exhibition.

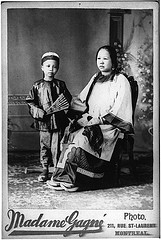

Made up of 107 photographs, it covered more than a century of the history of the community from 1867 to the mid-1980s. Archive photographs from several private collectors, the Notman Photographic Archives, the City of Montreal, Canadian Pacific, and la Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec made up the bulk of the exhibit. Portraiture dominated the subject matter though there were some photographs of streets, buildings, festivals and processions through Chinatown. A few newspaper clippings completed that section, a couple of which were about the famous Chinese athlete, Willie Woo. May Woo, his sister, created a stir when she joined the Chinese Lawn Tennis Club in Montreal. She was the first woman to do so and it made the society page of the local newspaper. Another clipping announced the inauguration of the Chinese Masonic Temple on La Gauchetière Street (June 6, 1912). No less than three different photographs of this event made it into the paper. Adding contemporary clippings on the community would have served as an interesting counterpoint in terms of past and present coverage in the mainstream media.

The early portraits are almost a "who's who" of the Chinese community at that time. Most were taken in studios at the request of the sitter—something only the rich in any community could afford to do. Alongside these early pictures, a number of group photographs of partially or completely unidentified people form a marked contrast. In a photograph depicting two women, one stands while the other sits holding a young white girl on her lap. They wear clothing made of plain material, not the luxurious fabrics sported by the women in the other portraits. Identified only as "Chinese domestic workers in the McDonald Family, 1867," the anonymous photograph was presumably commissioned by Mr. McDonald and reveals much about the paternalistic relationship between these women and their employer.

A series of colour photographs, interiors and exteriors, taken by Suzanne Girard and Marik Boudreau complete the exhibition. Taken in the standard social documentary style, these pictures contextualize the archive section, particularly in trying to understand the impact that the containment of Montreal's Chinatown has had.

In the 1970s despite strong opposition from the community, large sections of Chinatown were expropriated by the government to build the Guy Favreau apartment, office and retail complex. Several other buildings were also demolished to widen some of the main streets in the area. Girard has documented this process, illustrating it especially well in "Guy Favreau, 1982." In the background of the photo, construction fences shield the gaping holes made to build the complex. Just in from the corner of La Gauchetière and St. Urbain streets stands a deep red four-storey pagoda that was a powerful symbol inside and outside the community. When work to widen St. Urbain began it was put in storage, where it remains to this day.

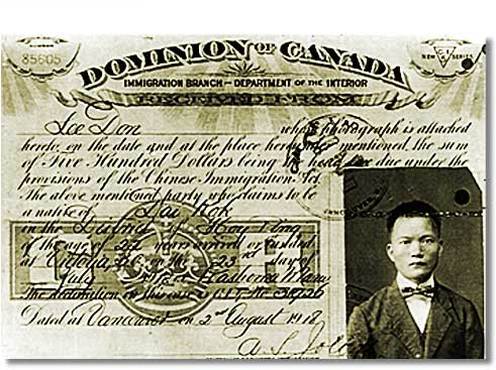

Boudreau's work features some intense portraiture. "La Gauchetière, 1980," taken on the street of the same name, shows an elderly woman sitting on some steps. She looks completely exhausted, a shopping bag at her feet. Nearby three young people, seemingly oblivious to her presence, are busy talking to one another. The photograph could be read as a comment on generational difference, but it also depicts the strong on-going tradition in the Chinese community of gathering in Chinatown on Sundays throughout the summer. The picture illustrates the changing nature of the community as a whole, in this case a particularly ironic one. About 70 per cent of Montreal's Chinatown is now made up of single older women. In the earlier part of this century, because of the head tax, the situation was reversed with young single men making up the majority of the community.

By exhibiting he photographs in Chinatown, more people from the community, particularly senior citizens, were able to see it. Prior to setting it up, organizers Suzanne Girard and Anita Malholtra had no idea of the impact of holding it there. In one case a Chinese-Canadian man in his 40s from out of town broke down in tears. Girard says he told her (through a translator) that he recognized his father in one of the images. Taken in a restaurant in March, 1940, the photograph shows a man cutting chicken on the left. HIs co-worker, with arms folded across his chest, looks into the camera with a faint smile on his lips. Because the photograph was taken with a flash, the light falls off a little on the edges. The man recognized his father a long scar on his forearm. His father had been dead for some years and the man had no photographs of him. Girard was able to give him the address of the archive, promising to help him obtain a copy of the picture.

This kind of interaction between the organizers and the community occurred many times during the three days. The names and histories of many people in the photographs who had been unknown were identified.

Published in Fuse Magazine, Fall 1990

The annual festival continues to be the main activity of InterCineArt, a group dedicated to promoting cross-cultural understanding. Teh festival's scope expands each year in terms of its programming. This year's edition featured over 80 films and videos from Hong Kong, Chinda, Taiwan, Canada, U.S., England and Japan.

The eclectic selection, which included documentaries, full-length features, commercial films and TV items from current affairs programs, was further augmented by a group of films made in the 1930s, '40s and '50s in mainland China, providing audiences with a rare chance to see some early masterpieces of Chinese cinema such as Yuan Muzhi's Street Angel (1937), Zheng Junli's Crows and Sparrows (1949) and Fate of a Graduate by Ying Yunei (1934).

The events of June 4, 1989 in Tianamen Square had a definite impact on this year's programming. Michael Gilson, who programmed with Cheung, says it was difficult not knowing what would be available. An attempt to get Black Snow by Xie Fei (1990), one fo the few films known to be made after June 4, failed. Samsara (dir. Huang Ianxin, 1989), screened this year to packed houses, has been banned by the Chinese government although it had received praise from the public. The film focuses on the disillusionment and later demise of Shi Ba, the son of a high-ranking official. The exact number of prints in circulation of Samsara is not known, but it is thought that the festival's copy is one of two or three presently not in China.

This year for the first time, part of the festival moved on to another city—six films were screened at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, Quebec. While the Secretary of State has encouraged the festival to expand, organizers say that expansion cannot proceed without increased funding.

During the year there are two grant-subsidized positions. These positions expanded to five during the festival. This year's festival would not have been possible without the volunteer labour of some 25 Montrealers of various backgrounds.

In a recent interview, Cheung voice some of her outstanding concerns, most of which centre on community involvement. Unlike many other film festivals, the FICCM has not experienced any major difficulties in attracting Chinese viewers and security in the on-going support and interest of Montreal's Asian communities. This year they averaged about 60 per cent of the audiences. Cheung would like to see greater involvement, however, at the organizational level and moves are being made in this regard. Closer bonds between FICCM and grassroots communities are becoming evident. As usual, the festival's schedule was published in full in The Chinese Press (the highest circulation Chinese language newspaper in Quebec). Posters and schedules were also distributed by hand in Chinatown.

This year's accompanying photo exhibition, Tang Ren Jie, looked at the history of Chinese presence in Montreal. Produced by InterCineArt, it was displayed outdoors in Chinatown for three days in Sun Yat-Sen Park and later moved indoors to Complexe Guy Favreau for 12 more days. All told, an estimated 8,000 people saw the exhibition.

Made up of 107 photographs, it covered more than a century of the history of the community from 1867 to the mid-1980s. Archive photographs from several private collectors, the Notman Photographic Archives, the City of Montreal, Canadian Pacific, and la Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec made up the bulk of the exhibit. Portraiture dominated the subject matter though there were some photographs of streets, buildings, festivals and processions through Chinatown. A few newspaper clippings completed that section, a couple of which were about the famous Chinese athlete, Willie Woo. May Woo, his sister, created a stir when she joined the Chinese Lawn Tennis Club in Montreal. She was the first woman to do so and it made the society page of the local newspaper. Another clipping announced the inauguration of the Chinese Masonic Temple on La Gauchetière Street (June 6, 1912). No less than three different photographs of this event made it into the paper. Adding contemporary clippings on the community would have served as an interesting counterpoint in terms of past and present coverage in the mainstream media.

The early portraits are almost a "who's who" of the Chinese community at that time. Most were taken in studios at the request of the sitter—something only the rich in any community could afford to do. Alongside these early pictures, a number of group photographs of partially or completely unidentified people form a marked contrast. In a photograph depicting two women, one stands while the other sits holding a young white girl on her lap. They wear clothing made of plain material, not the luxurious fabrics sported by the women in the other portraits. Identified only as "Chinese domestic workers in the McDonald Family, 1867," the anonymous photograph was presumably commissioned by Mr. McDonald and reveals much about the paternalistic relationship between these women and their employer.

A series of colour photographs, interiors and exteriors, taken by Suzanne Girard and Marik Boudreau complete the exhibition. Taken in the standard social documentary style, these pictures contextualize the archive section, particularly in trying to understand the impact that the containment of Montreal's Chinatown has had.

In the 1970s despite strong opposition from the community, large sections of Chinatown were expropriated by the government to build the Guy Favreau apartment, office and retail complex. Several other buildings were also demolished to widen some of the main streets in the area. Girard has documented this process, illustrating it especially well in "Guy Favreau, 1982." In the background of the photo, construction fences shield the gaping holes made to build the complex. Just in from the corner of La Gauchetière and St. Urbain streets stands a deep red four-storey pagoda that was a powerful symbol inside and outside the community. When work to widen St. Urbain began it was put in storage, where it remains to this day.

Boudreau's work features some intense portraiture. "La Gauchetière, 1980," taken on the street of the same name, shows an elderly woman sitting on some steps. She looks completely exhausted, a shopping bag at her feet. Nearby three young people, seemingly oblivious to her presence, are busy talking to one another. The photograph could be read as a comment on generational difference, but it also depicts the strong on-going tradition in the Chinese community of gathering in Chinatown on Sundays throughout the summer. The picture illustrates the changing nature of the community as a whole, in this case a particularly ironic one. About 70 per cent of Montreal's Chinatown is now made up of single older women. In the earlier part of this century, because of the head tax, the situation was reversed with young single men making up the majority of the community.

By exhibiting he photographs in Chinatown, more people from the community, particularly senior citizens, were able to see it. Prior to setting it up, organizers Suzanne Girard and Anita Malholtra had no idea of the impact of holding it there. In one case a Chinese-Canadian man in his 40s from out of town broke down in tears. Girard says he told her (through a translator) that he recognized his father in one of the images. Taken in a restaurant in March, 1940, the photograph shows a man cutting chicken on the left. HIs co-worker, with arms folded across his chest, looks into the camera with a faint smile on his lips. Because the photograph was taken with a flash, the light falls off a little on the edges. The man recognized his father a long scar on his forearm. His father had been dead for some years and the man had no photographs of him. Girard was able to give him the address of the archive, promising to help him obtain a copy of the picture.

This kind of interaction between the organizers and the community occurred many times during the three days. The names and histories of many people in the photographs who had been unknown were identified.

Published in Fuse Magazine, Fall 1990