Régards

In search of the 20th century man : Denis Fèlix

Alliance Française

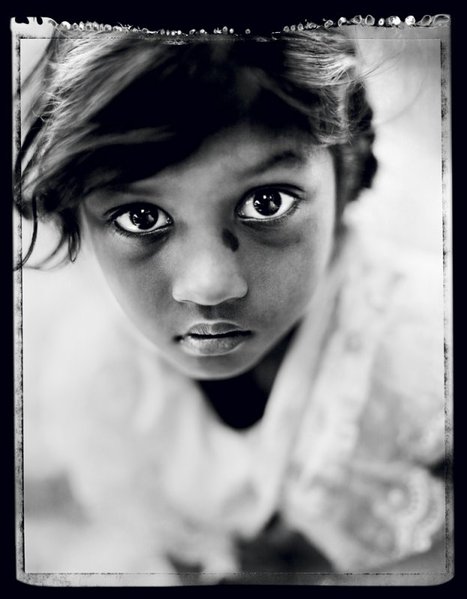

Ile Maurice. Copyright Denis Fèlix. Courtesy denisfelix.com

The old woman wears a pale cloth, wrapped closely over and around her head. Trimmed with thin dark-coloured brocade, the scarf's whiteness is so delicate and diaphanous, it seems to shimmer. To describe her skin as black would be a lie. Wrinkled and careworn, its myriad tones seem to all find a place in this black and white photograph. The photographic tonal range has been stretched to its furthest technical limit. It's a close up, just her head and neck. Her fine dark eyes, glistening in the light with reflections, are slightly narrowed.

What did she make of Denis Fèlix, the 40 year-old photographer from France?

This is one of thirty-one photographs, without titles, taken from a larger selection called Regards. Made from large format black-and-white Polaroid film approximately 11" x 14", Fèlix presents us with contact prints (Contact printing recalls photography's earliest days. Prints were literally made (in a darkroom) by projecting the light onto the entire negative sheet in direct contact with light-sensitive paper. The prints were the same size and shape as the negatives. Enlargements, a later invention, meant projecting the light through the negative at a distance from the paper.).

Traveling through parts of South Africa, Guinea, Mali, Morocco, the Caribbean, "the shores of the Indian Ocean," as the statement, unsigned, accompanying the exhibition states, and France, Fèlix works with his large camera and tripod, a portable backdrop and laboratory. Most of the images are portraits, usually shot very tightly, focusing on the person's face and head. The rest consist of photographs of hands and objects, bent engraved forks for instance, or hands holding a large pair of aged scissors.

Shot in this particular style and format, the words "ethnographic" and "anthropological" come to mind. Fèlix is the latest in a long line of Western photographers who have set out to photograph "lost" or "primitive tribes"—Irving Penn and Leni Riefenstahl, to name only two.

"Thus photographed," the exhibition statement continues, "They shed light on the social and cultural context of the subjects whom Denis Fèlix has encountered throughout his travels .... This is a context Denis Fèlix knows well, having stayed with their families, in their tribes, and penetrated their infrastructures long enough to be incorporated into their lives."

Perhaps Fèlix didn't stay long enough to remember his sitters' names or if he knows them, he didn't bother to tell us. As for words like "penetrated" and "incorporated," they sound appropriate to some hostile corporate takeover, not the attempt to take dignified sensitive portraits of strangers. For ultimately, despite the photographs' beauty and intrinsic richness as portraits, that's what Fèlix's presentation tends to smack of.

Untitled, nameless, and unknown even in their geographic location, as viewers we are given nothing but the images as information about the individual people. In the context of the press release, each is transformed into an ethnographic "type". It's a shame, since many testify both to the potency of the sitter and the photographer.

Gaining access to the homes and lives of individuals in the Third World is no difficult undertaking for a white man from Europe with a big camera. One can only hope that while he was "penetrating their infrastructures" he didn't abuse peoples' generosity and trust.

The exhibition statement babbles on about "populations" and "tribes" while calling his approach "quasi-anthropological", suggesting "the medical training of the photographer is obvious...." For myself, I saw nothing to suggest such training. Rather, obviously Fèlix has worked commercially, something confirmed in the resumé posted on his web site.

With watch-size cameras now available, using a hulking large format one is a deliberate choice. It's the very limits of this purists' medium that can deliver such remarkable results, something well known by commercial photographers. It allows for far more control than smaller formats, something this thirteen-year veteran of fashion and other commercial photography clearly understands. Controlling tonal ranges, especially in black and white, reducing graininess, and being far more thoughtful about subjects represent only some of the benefits. Presenting contact prints forces the photographer to be much more careful at the outset, while photographing, as opposed to later on in the darkroom, where if enlarged, images can be cropped.

"To date, Denis Fèlix has captured the social and cultural essence of many countries," the resumé on his web site claims. Fèlix sets out to "capture" "races" on the verge of "extinction". Some unsmiling sitters look fairly anxious. Perhaps it's because they've just read his exhibition statement (What would they make of it, I wonder.). His heart may be in the right place but an effort to remember names and be a little more transparent and less arrogant wouldn't hurt. For all that, look carefully at the pictures, and you won't be disappointed. A photographer so technically skilled with rapport of some kind with strangers commands attention.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000

What did she make of Denis Fèlix, the 40 year-old photographer from France?

This is one of thirty-one photographs, without titles, taken from a larger selection called Regards. Made from large format black-and-white Polaroid film approximately 11" x 14", Fèlix presents us with contact prints (Contact printing recalls photography's earliest days. Prints were literally made (in a darkroom) by projecting the light onto the entire negative sheet in direct contact with light-sensitive paper. The prints were the same size and shape as the negatives. Enlargements, a later invention, meant projecting the light through the negative at a distance from the paper.).

Traveling through parts of South Africa, Guinea, Mali, Morocco, the Caribbean, "the shores of the Indian Ocean," as the statement, unsigned, accompanying the exhibition states, and France, Fèlix works with his large camera and tripod, a portable backdrop and laboratory. Most of the images are portraits, usually shot very tightly, focusing on the person's face and head. The rest consist of photographs of hands and objects, bent engraved forks for instance, or hands holding a large pair of aged scissors.

Shot in this particular style and format, the words "ethnographic" and "anthropological" come to mind. Fèlix is the latest in a long line of Western photographers who have set out to photograph "lost" or "primitive tribes"—Irving Penn and Leni Riefenstahl, to name only two.

"Thus photographed," the exhibition statement continues, "They shed light on the social and cultural context of the subjects whom Denis Fèlix has encountered throughout his travels .... This is a context Denis Fèlix knows well, having stayed with their families, in their tribes, and penetrated their infrastructures long enough to be incorporated into their lives."

Perhaps Fèlix didn't stay long enough to remember his sitters' names or if he knows them, he didn't bother to tell us. As for words like "penetrated" and "incorporated," they sound appropriate to some hostile corporate takeover, not the attempt to take dignified sensitive portraits of strangers. For ultimately, despite the photographs' beauty and intrinsic richness as portraits, that's what Fèlix's presentation tends to smack of.

Untitled, nameless, and unknown even in their geographic location, as viewers we are given nothing but the images as information about the individual people. In the context of the press release, each is transformed into an ethnographic "type". It's a shame, since many testify both to the potency of the sitter and the photographer.

Gaining access to the homes and lives of individuals in the Third World is no difficult undertaking for a white man from Europe with a big camera. One can only hope that while he was "penetrating their infrastructures" he didn't abuse peoples' generosity and trust.

The exhibition statement babbles on about "populations" and "tribes" while calling his approach "quasi-anthropological", suggesting "the medical training of the photographer is obvious...." For myself, I saw nothing to suggest such training. Rather, obviously Fèlix has worked commercially, something confirmed in the resumé posted on his web site.

With watch-size cameras now available, using a hulking large format one is a deliberate choice. It's the very limits of this purists' medium that can deliver such remarkable results, something well known by commercial photographers. It allows for far more control than smaller formats, something this thirteen-year veteran of fashion and other commercial photography clearly understands. Controlling tonal ranges, especially in black and white, reducing graininess, and being far more thoughtful about subjects represent only some of the benefits. Presenting contact prints forces the photographer to be much more careful at the outset, while photographing, as opposed to later on in the darkroom, where if enlarged, images can be cropped.

"To date, Denis Fèlix has captured the social and cultural essence of many countries," the resumé on his web site claims. Fèlix sets out to "capture" "races" on the verge of "extinction". Some unsmiling sitters look fairly anxious. Perhaps it's because they've just read his exhibition statement (What would they make of it, I wonder.). His heart may be in the right place but an effort to remember names and be a little more transparent and less arrogant wouldn't hurt. For all that, look carefully at the pictures, and you won't be disappointed. A photographer so technically skilled with rapport of some kind with strangers commands attention.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000