Ousmane Sow

National Gallery of Canada Plaza

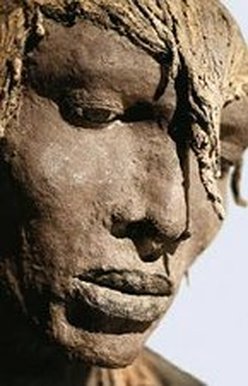

Closeup Massaï warrior. Copyright www.ousmanesow.com

They are giants. Somehow related to the clay sculptures that came to life in the Sinbad movies made in the fifties or sixties, Ousmane Sow's twenty something figurative works feel like they just sprang out of the ground onto the low grey wood just outside the National Gallery of Canada.

Capturing scenes from what was once(?) or still is the daily life of three of Africa's tribes—the Peulh (1993-1994), the Nouba (1984-1987) and the Massaï (1988-1989)—Sow uses an alchemy, a medium designed by himself to create his figures. Larger than life, the sometimes over two metre high figures, with rippling muscles indicative of the harshness of life lived traditionally by these peoples, Sow destroys an entire set of stereotypes through their faces. The size and strength of the figures would easily lead viewers to expect some kind of violence or dominance to show in the figures' faces. But contrary to what our culture (at least) conditions us to believe, the faces of Sow's figures are calm, contemplative, thoughtful. Perhaps the most surprising of these (for me) is Standing Warrior (one of the Massaï).

At least nine feet high, the warrior stands with arms apart carrying a tall shield and a spear in each hand wearing only a loincloth. He literally stretches up over most viewers, and with his elongated ears and head tilted forward, he quietly looks at the ground. After looking at his remarkable body, his face comes as an extraordinary window into the mysteries of what this warrior's thoughts might be and the landscape he is confronting. (By the way, I did see more than a few women and gay men(?), chuckling or smiling as they looked at Sow's work.)

Sow's training as a physiologist shows in every inch of these deceptively simple yet incredibly detailed and complex works. To represent figures of such scale well in such a wide variety of positions and postures, doing everything from participating in scarification ceremonies, wrestling, sacrificing animals, breastfeeding, and drumming for instance, requires an expansive knowledge of the human body and how it works. If not that, then at least many many many hours of close observation of the human form. Sow's medical knowledge clearly plays a dramatic role in his sculpture technique.

Sometimes it is possible to see the network of gauze below the layers of clay or plaster or mud that Sow has used. Although most of the works are of varying tones of dark clay and brown, the most recent series (The Peuhl) also uses a dull almost verdigris shade of green.

In 1999, Sow held two extraordinary exhibitions of a series of works on the subject of the Battle of Little Big Horn. Consisting of twenty-three figures, in Paris the works were shown moving across a bridge. In Africa, the sculptures were shown in Dakar (Senegal) at the site of the Gorée Memorial (Gorée island is notorious for its use as a holding cell for millions of Africans sold into the Atlantic slave trade.)

Born in 1935, Sow held his first exhibition at the age of fifty. He joins the small but internationally renowned group of Senegalese artists, known primarily for their brilliance in storytelling and visualization. Filmmaker Idrissa Ouedraogo and writer and filmmaker Sembene Ousmane for instance. Using non-professional actors and members of his extended family, Ouedraogo made the internationally acclaimed films Yaaba and Tilaii. Xala(The Curse, 1974) is perhaps Sembene Ousmane's most famous film. (It and other African films are available at Invisible Cinema, 319 Lisgar, 237-0769).

Sow's work stands as a testament to the starkness of lives carved out by what we may see as harsh daily work, but the work is also witness to human lives not quite robbed of the symbolic and the meaningful ritual, and face-to-face human interaction.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2001

Capturing scenes from what was once(?) or still is the daily life of three of Africa's tribes—the Peulh (1993-1994), the Nouba (1984-1987) and the Massaï (1988-1989)—Sow uses an alchemy, a medium designed by himself to create his figures. Larger than life, the sometimes over two metre high figures, with rippling muscles indicative of the harshness of life lived traditionally by these peoples, Sow destroys an entire set of stereotypes through their faces. The size and strength of the figures would easily lead viewers to expect some kind of violence or dominance to show in the figures' faces. But contrary to what our culture (at least) conditions us to believe, the faces of Sow's figures are calm, contemplative, thoughtful. Perhaps the most surprising of these (for me) is Standing Warrior (one of the Massaï).

At least nine feet high, the warrior stands with arms apart carrying a tall shield and a spear in each hand wearing only a loincloth. He literally stretches up over most viewers, and with his elongated ears and head tilted forward, he quietly looks at the ground. After looking at his remarkable body, his face comes as an extraordinary window into the mysteries of what this warrior's thoughts might be and the landscape he is confronting. (By the way, I did see more than a few women and gay men(?), chuckling or smiling as they looked at Sow's work.)

Sow's training as a physiologist shows in every inch of these deceptively simple yet incredibly detailed and complex works. To represent figures of such scale well in such a wide variety of positions and postures, doing everything from participating in scarification ceremonies, wrestling, sacrificing animals, breastfeeding, and drumming for instance, requires an expansive knowledge of the human body and how it works. If not that, then at least many many many hours of close observation of the human form. Sow's medical knowledge clearly plays a dramatic role in his sculpture technique.

Sometimes it is possible to see the network of gauze below the layers of clay or plaster or mud that Sow has used. Although most of the works are of varying tones of dark clay and brown, the most recent series (The Peuhl) also uses a dull almost verdigris shade of green.

In 1999, Sow held two extraordinary exhibitions of a series of works on the subject of the Battle of Little Big Horn. Consisting of twenty-three figures, in Paris the works were shown moving across a bridge. In Africa, the sculptures were shown in Dakar (Senegal) at the site of the Gorée Memorial (Gorée island is notorious for its use as a holding cell for millions of Africans sold into the Atlantic slave trade.)

Born in 1935, Sow held his first exhibition at the age of fifty. He joins the small but internationally renowned group of Senegalese artists, known primarily for their brilliance in storytelling and visualization. Filmmaker Idrissa Ouedraogo and writer and filmmaker Sembene Ousmane for instance. Using non-professional actors and members of his extended family, Ouedraogo made the internationally acclaimed films Yaaba and Tilaii. Xala(The Curse, 1974) is perhaps Sembene Ousmane's most famous film. (It and other African films are available at Invisible Cinema, 319 Lisgar, 237-0769).

Sow's work stands as a testament to the starkness of lives carved out by what we may see as harsh daily work, but the work is also witness to human lives not quite robbed of the symbolic and the meaningful ritual, and face-to-face human interaction.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2001