Just the Facts?

Contemporary Documentary Approaches

Patrick Altman, David Askevold, June Clark,

Carole Condé/Karl Beveridge, Vid Inglelevics, Mark Lewis,

Brenda Pelkey, Jane Ash Poitras, Henri Robideau, Jayce Salloum

Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography

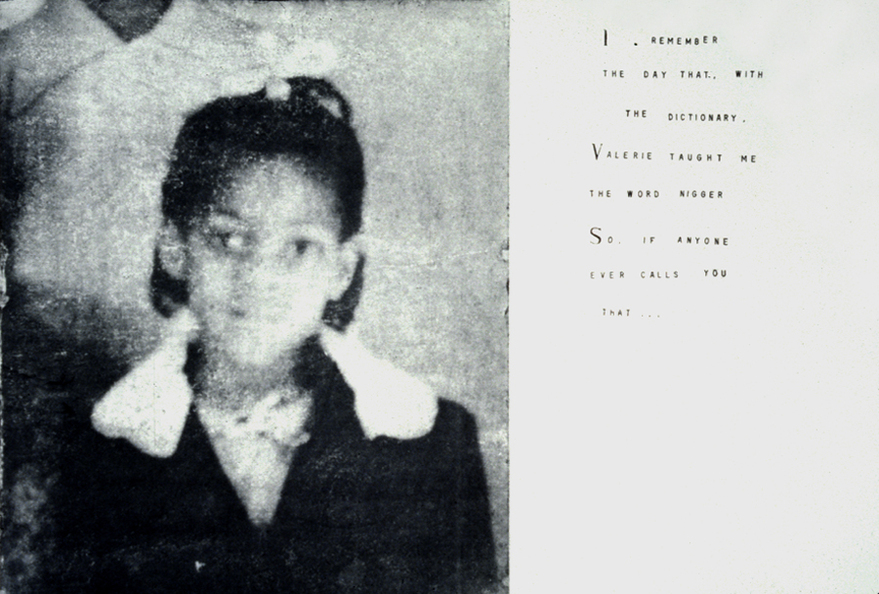

Part of Formative Triptych, 1990, June Clark. Copyright June Clark, courtesy www.juneclark.ca

"Formative Triptych" (1989) by June Clark. In the first image, a young Black girl with her hair in a pigtail, smiles out of the wall next to the following text: "I remember that, with the dictionary, Valerie taught me the word nigger - 'So, if anyone ever calls you that....'" I stood there imagining this little girl having her innocence shattered by her mother, her aunt, or her older sister.

Just the Facts? presents a relative feast of work not usually on the menu of the CMCP or any museum for that matter. Exploring issues around race, colonialism and representation, some of it is also actually by people of colour and/or of native ancestry too. The latter is definitely cause for raising a pint since, still, it occurs so rarely.

Thematically work falling outside these parameters seemed added on as an afterthought, almost to please those who perhaps might be tempted to dismiss the rest of it as "trendy". Some work seems quite dated, regardless of when it was produced, notably David Askevold, Jane Ash Poitras, and Brenda Pelkey's work.

June Clark's deceptively simple text and photographic etchings resonate with unwritten, unspoken personal stories. Using imagery reminiscent of photo booths—frontal head and shoulder shots—her "Formative Triptych" (1989) is a strong example. The approximately 24" x 32" out of focus grainy images look like richly textured old maps.

Is this "documentary photography"? Surely, since it documents the things people of colour don't often talk about—the necessary destruction of a child's innocence. This is about life insurance and survival. Clark creates a visual representation referencing colonial history and racial politics without being didactic, overly ideological and removing the experience from what it is—deeply rooted in the personal, individual and subjective. And yet, she's also shown it as it is—universally human. Who can't relate to the innocence horrifically lost of a child?

Similarly, the third image of an older Black woman with what looks like a wild flowery shirt on, next to: "I decided that I must become so famous and so recognizable so that they could never let me die in an emergency room."

Language, who owns and controls it, dominates Vid Ingelevics work. Laying out slices of his Latvian family's history as Displaced Persons in Germany after World War II, Ingelevics assembled official papers, photographs and an installation (filing cabinet, desk and chair). Framed in wooden closet-like structures, it's treachery to think these images ordinary. The text with the images emphasizes the incongruity and haunting coincidences between his often surreal experiences, "official histories" and what people say (or don't) to him. For some, in this case, some of the Germans Ingelevics met, "Denial aint just the name of a river in Egypt," as Mark Twain wrote. The forms that denial takes are simply fascinating, especially since it's all overlaid like a shroud by Ingelevics self-acknowledged not so great German.

He's trying to read a story told in the language of another tribe. His is a post-colonial role reversal, where the colonial subject is empowered to go back—and seek answers.

His photography is perfectly fine architectural work with nothing particularly extraordinary about it. The extraordinary emerges from the images' being interwoven with descriptions of how he worked—things as simple as positioning a door. We're in on at least part of the photographer's manipulation of the subject. This adds yet another layer of rancid icing to this rotting cake of history.

Next to a photograph of a large black tombstone with the names of several family members inscribed on it, he describes going back multiple times, to find the best light to photograph it. Finally, he realizes, because of its location, "the words on the stone were never lit by the sun."

I left his work with the stench of the decaying layer-cake still in my nostrils. Only to move on, to another historical site—Henri Robideau's work. Entitled, "500 Fun Years" (1992), Robideau's fantastic caustic dry wit, keen sense of the ridiculous and ability to empathize have lost nothing in the years since his images of "giant things", usually "giant" political demonstrations. In this series he acknowledged to me, a sense of humour was the most difficult thing to maintain. One of Robideau's grandmothers was Mohawk. Inspired and revolted by an ad he saw selling trips to the Caribbean on the quincentenary of Columbus' 1492 field trip, Robideau photographed political demonstrations around native issues, Oka for instance, as well as "native" mannequins in museum displays.

Made up of 16" x 20" prints, the panoramas are interspersed with large single frame images, forming a more humourous counterpoint. Like the panoramas—single images spliced together at angles, the planes matched up almost seamlessly—the single images anchor the viewer to the photographic process just as obviously. His prints include part of the sprocket holes at the edge of the negative.

Under one tableaux, Robideau writes on the image, "Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the founder of Montreal, puts the finishing touch on a real estate deal with the Mohawks". In the tableaux, a Mohawk man, arm upraised makes a last grab at de Chomedey's chest as de Chomedey shoots him.

Robideau contrasts the real and the unreal, mirroring the very process of photographic image-making—the manipulation of reality to represent a single image chained to a point of view, specific time and space, that is supposedly "objective".

Except as with Jayce Salloum's disquieting and brilliant "(sites+) demarcations" (1992-94), the camera has changed hands. Salloum not only questions the historical representations of Lebanon, he fearlessly calls into question his own. It's for the colonized subject to discover whether a medium with a propensity for and history of objectifying and exoticising difference can be used to tell our stories. Ultimately the strongest work reflects at least two ancient and beautiful human traits that colonization did not destroy: the ability to imagine and the need to represent the imagination's wonderings and wanderings.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000

Just the Facts? presents a relative feast of work not usually on the menu of the CMCP or any museum for that matter. Exploring issues around race, colonialism and representation, some of it is also actually by people of colour and/or of native ancestry too. The latter is definitely cause for raising a pint since, still, it occurs so rarely.

Thematically work falling outside these parameters seemed added on as an afterthought, almost to please those who perhaps might be tempted to dismiss the rest of it as "trendy". Some work seems quite dated, regardless of when it was produced, notably David Askevold, Jane Ash Poitras, and Brenda Pelkey's work.

June Clark's deceptively simple text and photographic etchings resonate with unwritten, unspoken personal stories. Using imagery reminiscent of photo booths—frontal head and shoulder shots—her "Formative Triptych" (1989) is a strong example. The approximately 24" x 32" out of focus grainy images look like richly textured old maps.

Is this "documentary photography"? Surely, since it documents the things people of colour don't often talk about—the necessary destruction of a child's innocence. This is about life insurance and survival. Clark creates a visual representation referencing colonial history and racial politics without being didactic, overly ideological and removing the experience from what it is—deeply rooted in the personal, individual and subjective. And yet, she's also shown it as it is—universally human. Who can't relate to the innocence horrifically lost of a child?

Similarly, the third image of an older Black woman with what looks like a wild flowery shirt on, next to: "I decided that I must become so famous and so recognizable so that they could never let me die in an emergency room."

Language, who owns and controls it, dominates Vid Ingelevics work. Laying out slices of his Latvian family's history as Displaced Persons in Germany after World War II, Ingelevics assembled official papers, photographs and an installation (filing cabinet, desk and chair). Framed in wooden closet-like structures, it's treachery to think these images ordinary. The text with the images emphasizes the incongruity and haunting coincidences between his often surreal experiences, "official histories" and what people say (or don't) to him. For some, in this case, some of the Germans Ingelevics met, "Denial aint just the name of a river in Egypt," as Mark Twain wrote. The forms that denial takes are simply fascinating, especially since it's all overlaid like a shroud by Ingelevics self-acknowledged not so great German.

He's trying to read a story told in the language of another tribe. His is a post-colonial role reversal, where the colonial subject is empowered to go back—and seek answers.

His photography is perfectly fine architectural work with nothing particularly extraordinary about it. The extraordinary emerges from the images' being interwoven with descriptions of how he worked—things as simple as positioning a door. We're in on at least part of the photographer's manipulation of the subject. This adds yet another layer of rancid icing to this rotting cake of history.

Next to a photograph of a large black tombstone with the names of several family members inscribed on it, he describes going back multiple times, to find the best light to photograph it. Finally, he realizes, because of its location, "the words on the stone were never lit by the sun."

I left his work with the stench of the decaying layer-cake still in my nostrils. Only to move on, to another historical site—Henri Robideau's work. Entitled, "500 Fun Years" (1992), Robideau's fantastic caustic dry wit, keen sense of the ridiculous and ability to empathize have lost nothing in the years since his images of "giant things", usually "giant" political demonstrations. In this series he acknowledged to me, a sense of humour was the most difficult thing to maintain. One of Robideau's grandmothers was Mohawk. Inspired and revolted by an ad he saw selling trips to the Caribbean on the quincentenary of Columbus' 1492 field trip, Robideau photographed political demonstrations around native issues, Oka for instance, as well as "native" mannequins in museum displays.

Made up of 16" x 20" prints, the panoramas are interspersed with large single frame images, forming a more humourous counterpoint. Like the panoramas—single images spliced together at angles, the planes matched up almost seamlessly—the single images anchor the viewer to the photographic process just as obviously. His prints include part of the sprocket holes at the edge of the negative.

Under one tableaux, Robideau writes on the image, "Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the founder of Montreal, puts the finishing touch on a real estate deal with the Mohawks". In the tableaux, a Mohawk man, arm upraised makes a last grab at de Chomedey's chest as de Chomedey shoots him.

Robideau contrasts the real and the unreal, mirroring the very process of photographic image-making—the manipulation of reality to represent a single image chained to a point of view, specific time and space, that is supposedly "objective".

Except as with Jayce Salloum's disquieting and brilliant "(sites+) demarcations" (1992-94), the camera has changed hands. Salloum not only questions the historical representations of Lebanon, he fearlessly calls into question his own. It's for the colonized subject to discover whether a medium with a propensity for and history of objectifying and exoticising difference can be used to tell our stories. Ultimately the strongest work reflects at least two ancient and beautiful human traits that colonization did not destroy: the ability to imagine and the need to represent the imagination's wonderings and wanderings.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000