Stan Douglas : Le Détroit

Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography

Photograph copyright Stan Douglas, Detroit

In a mere 28 images, Stan Douglas pries open a festering issue in North American cities and in photography - the so-called "documentary photography" of urban decay.

In photography, this is an old old theme. In its earliest days, the impact of having seen nothing like it before gave it enormous force in social movements for change. New Yorker, Jacob Riis, a former police reporter, can perhaps be credited with its first major exploitation. In his remarkable book published in 1890, How the Other Half Lives, Riis, used the latest advances in flash technology to photograph the dispossessed inhabitants of New York's lower East side and their decrepit surroundings. Photographs, "documentary proof" of such barbaric living conditions, could hardly be ignored. Riis discovered how much more commanding they were than mere words.

Douglas sits on the fence of this tradition except that his photographs are virtually people-less. Did Douglas fear photographing the people who live in and around these sites? Did he fear that doing so would be exploitative?

Over a hundred years after Riis' book, public knowledge and understanding of the medium has grown immensely, in part because of public access and widespread use of the medium. Arguably, far more is understood about the medium's intrinsic abilities to distort and manipulate than in Riis' day.

Hailing from Vancouver, Douglas spent several years researching and photographing sites in Detroit well past their prime, some considerably in the throes of being reclaimed, as it were, by nature.

Conversely, lavish and expansive, these huge colour prints (the largest, approximately 40" x 20"), shot with a 2 1/4" and a panoramic large format camera, are unforgiving and surreal. People-less, they often feature painterly skies, replete with clouds, subtle shifts in colour, shade, and hue. Douglas serves up picture postcard Wizard of Oz-like settings, except the destination is lacking and doesn't follow a Yellow Brick Road.

The dilapidated, the worn, the wreck—this is Douglas' subject. The plight of inner city America, known to most Canadians, makes its appearance here not in faces of people doomed to live there but in the seemingly empty abandoned buildings themselves.

Douglas' work invokes an odd photographic lineage. For it also recalls the slew of European and American photographers who traveled the world in the 19th century, documenting the ruins of ancient civilizations. A single human figure was often used in such work, to give the viewers a sense of scale. Perhaps Douglas' utter rejection of this trademark is another deliberate paradox. (One of the 28 images shows a solitary person, huddling in a bus shelter in the distance.).

How do America and its "ancient monuments" stack up against the great pyramids and the Sphinx at Giza, for instance?

"Artists are the shock-troops of gentrification." Douglas' work recalls a bit of graffiti I'd seen in Montreal many years ago, paradoxically a city continuing to suffer from this phenomenon. Crudely plastered across the wall of a local university's Fine Arts building, in all probability, the spray paint itself was the work of a Fine Arts student.

It's curious to consider where Douglas would stand viz-à-viz this statement. In his photography, does he declaim the decay of the buildings, some historic? Or does he deplore the wretchedness of those living in and amongst them? And what is his aim—if any? To have the buildings converted into high-price condos?

For Douglas most brilliantly makes ample use of the medium's limitless gifts for metamorphosing the ugly, the deplorable and the horrific into the stunningly beautiful. Douglas, literally, waited for the best possible light.

The vacuous and banal of North American metropolitan life parades around the edges of the sometimes gouged out, sometimes formerly great, crumbling architectural wrecks. Details like stunted weeds, cracks in concrete paving, empty petrol pumps, broken windows, "no entry" signs, seemingly pre-fabricated identical homes...it's enough to incite the most reluctant suburbanite, numbed by the commute, routine, uniformity and rigidity of burb life, to feel righteous or even blessed.

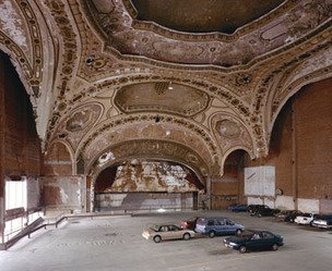

"Michigan Theatre 1997/98" presents us with an extreme example. The former theatre's domed roof, encrusted on the inside with Greco-Roman figurative, foliage, and scroll work, rolls down to a half oval shape, blacked out, (formerly the theatre's stage). All around it, the roof work has been cut off at its legs. Its russet and cream colour schemes, blackened, chipped, and cracked with dust and age, all ending unevenly around the inside of the building.

At the bottom lies the most unexpected thing of all—a parking lot.

Poured with precision, the concrete stretches out, replete with its own feeble attempts at adornment—yellow lines separating parking spaces, numbered in the same dulling yellow shade. And on top of this, nestle a handful of the omnipotent - cars.

A quick glance at the Comments book at the CMCP reveals several variations on the following opinion: loved the show, beautiful pictures...but would never want to live in Detroit.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000

In photography, this is an old old theme. In its earliest days, the impact of having seen nothing like it before gave it enormous force in social movements for change. New Yorker, Jacob Riis, a former police reporter, can perhaps be credited with its first major exploitation. In his remarkable book published in 1890, How the Other Half Lives, Riis, used the latest advances in flash technology to photograph the dispossessed inhabitants of New York's lower East side and their decrepit surroundings. Photographs, "documentary proof" of such barbaric living conditions, could hardly be ignored. Riis discovered how much more commanding they were than mere words.

Douglas sits on the fence of this tradition except that his photographs are virtually people-less. Did Douglas fear photographing the people who live in and around these sites? Did he fear that doing so would be exploitative?

Over a hundred years after Riis' book, public knowledge and understanding of the medium has grown immensely, in part because of public access and widespread use of the medium. Arguably, far more is understood about the medium's intrinsic abilities to distort and manipulate than in Riis' day.

Hailing from Vancouver, Douglas spent several years researching and photographing sites in Detroit well past their prime, some considerably in the throes of being reclaimed, as it were, by nature.

Conversely, lavish and expansive, these huge colour prints (the largest, approximately 40" x 20"), shot with a 2 1/4" and a panoramic large format camera, are unforgiving and surreal. People-less, they often feature painterly skies, replete with clouds, subtle shifts in colour, shade, and hue. Douglas serves up picture postcard Wizard of Oz-like settings, except the destination is lacking and doesn't follow a Yellow Brick Road.

The dilapidated, the worn, the wreck—this is Douglas' subject. The plight of inner city America, known to most Canadians, makes its appearance here not in faces of people doomed to live there but in the seemingly empty abandoned buildings themselves.

Douglas' work invokes an odd photographic lineage. For it also recalls the slew of European and American photographers who traveled the world in the 19th century, documenting the ruins of ancient civilizations. A single human figure was often used in such work, to give the viewers a sense of scale. Perhaps Douglas' utter rejection of this trademark is another deliberate paradox. (One of the 28 images shows a solitary person, huddling in a bus shelter in the distance.).

How do America and its "ancient monuments" stack up against the great pyramids and the Sphinx at Giza, for instance?

"Artists are the shock-troops of gentrification." Douglas' work recalls a bit of graffiti I'd seen in Montreal many years ago, paradoxically a city continuing to suffer from this phenomenon. Crudely plastered across the wall of a local university's Fine Arts building, in all probability, the spray paint itself was the work of a Fine Arts student.

It's curious to consider where Douglas would stand viz-à-viz this statement. In his photography, does he declaim the decay of the buildings, some historic? Or does he deplore the wretchedness of those living in and amongst them? And what is his aim—if any? To have the buildings converted into high-price condos?

For Douglas most brilliantly makes ample use of the medium's limitless gifts for metamorphosing the ugly, the deplorable and the horrific into the stunningly beautiful. Douglas, literally, waited for the best possible light.

The vacuous and banal of North American metropolitan life parades around the edges of the sometimes gouged out, sometimes formerly great, crumbling architectural wrecks. Details like stunted weeds, cracks in concrete paving, empty petrol pumps, broken windows, "no entry" signs, seemingly pre-fabricated identical homes...it's enough to incite the most reluctant suburbanite, numbed by the commute, routine, uniformity and rigidity of burb life, to feel righteous or even blessed.

"Michigan Theatre 1997/98" presents us with an extreme example. The former theatre's domed roof, encrusted on the inside with Greco-Roman figurative, foliage, and scroll work, rolls down to a half oval shape, blacked out, (formerly the theatre's stage). All around it, the roof work has been cut off at its legs. Its russet and cream colour schemes, blackened, chipped, and cracked with dust and age, all ending unevenly around the inside of the building.

At the bottom lies the most unexpected thing of all—a parking lot.

Poured with precision, the concrete stretches out, replete with its own feeble attempts at adornment—yellow lines separating parking spaces, numbered in the same dulling yellow shade. And on top of this, nestle a handful of the omnipotent - cars.

A quick glance at the Comments book at the CMCP reveals several variations on the following opinion: loved the show, beautiful pictures...but would never want to live in Detroit.

Published in The Ottawa Xpress, 2000